Engineering iPSC Brain-Organoid Networks on MaxOne HD-MEA

"I would highlight the flexibility to program the system exactly the way you want. That level of customization is powerful, yet everything remains simple and seamless from the computer. It's a rare combination of power and ease of use."

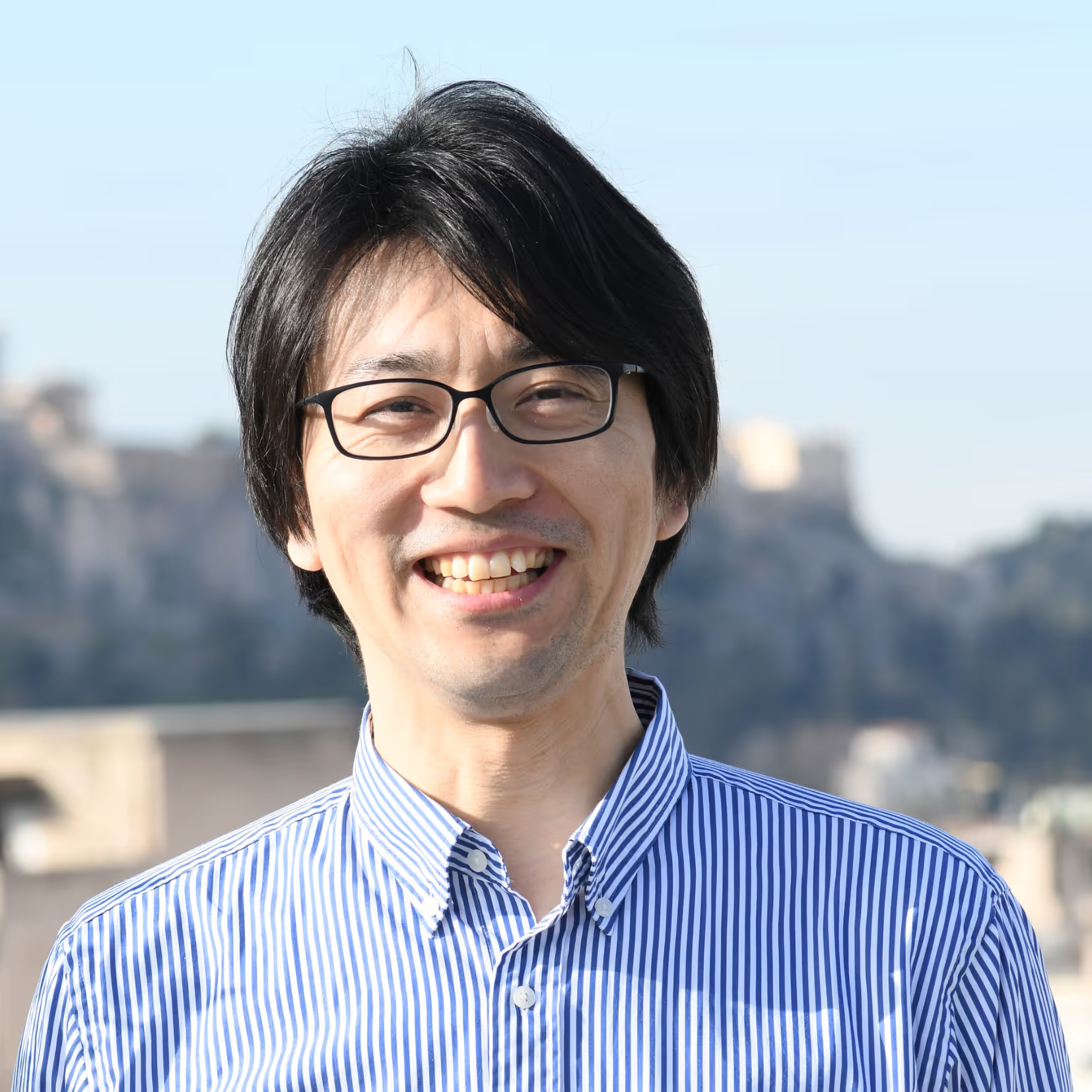

Recently at the ISSCR Neural Stem Cell Symposium in Athens, Greece, we had the pleasure of catching up with Prof. Yoshiho Ikeuchi, a leading researcher in the field of neural networks from The University of Tokyo, Japan. Over freddo cappuccinos in this historic city, it was the perfect setting to delve deeper into his experience with our MaxOne HD-MEA System and the newly launched MaxOne+ chips.

Prof. Ikeuchi shared valuable insights into how our technology support his advanced research, particularly in studying complex in-vitro organoid models of inter-regional neural networks. He also spoke about the impact of high-resolution electrophysiological recordings on understanding brain function and circuit development.

It was a privilege to hear firsthand how our HD-MEA systems contribute to pioneering work like his, and we look forward to continuing this exciting collaboration.

In this

conversation

What inspired you to become a scientist?

I've always been drawn to science, even from a young age. As a kid, I was constantly exposed to different scientific topics, especially space, which really captured my imagination. I remember thinking how fascinating science was and knew early on that I wanted to pursue something in that field. It wasn’t until high school, though, that I discovered my passion for molecular biology. That’s when things really clicked for me, and it’s still the area I’m most passionate about today.

And from space and molecular biology, how did you get to neuroscience?

In graduate school, I was focused on fundamental biology, particularly studying modifications of transfer RNA. You know the codon table: three nucleotides correspond to one amino acid. I found that incredibly elegant. It felt like the essence of life: a clear, molecular code orchestrating a highly complex process between just two types of molecules.

But then I looked at neurons, on the complete opposite end of the complexity spectrum. Neurons are fascinating not just because of their intricate structures and long processes, but because they operate on such a localized level. They can respond to synaptic input at the level of individual synapses, not just across the whole cell. Numerous molecules including transfer RNAs orchestrate the complex subcellular events, which ultimately leads to the functions of the brain - That molecular-to-system multi-level complexity of the brain really drew me in. I think, in the end, I was inspired by the challenge.

This is so interesting! I had never thought of it as this spectrum. And now, from molecular biology to neuroscience, what is your primary research interest?

My main research focus is on constructing neural networks using brain organoids derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). But if I’m honest, the most important questions might be why I do this, and what I hope to learn or achieve through it.

There are a few key motivations behind this work. First, there's a fundamental curiosity: I want to better understand how the brain works. Second, I’m fascinated by how neurons navigate through tissue and establish the correct connections, how they find their way and wire themselves into functional circuits. Third, there’s a more futuristic ambition: the idea of building a biological computer from these networks.

And if I’m being completely transparent, there’s also just the sheer joy of working with organoids, growing them, experimenting with them, and seeing what new structures can be built. That creative, engineering-driven side of it might be a fourth reason. So while the original question might have seemed straightforward, the answer really reflects a blend of scientific curiosity, technical challenge, and playful exploration.

Science and engineering offer not just discovery, but also lots of fun, indeed!

Absolutely! That day-to-day sense of fun is essential in research. Sure, we all have overarching scientific goals guiding our work, but the experience of being a scientist is also about enjoying the process. Ideally, the bigger research questions and the daily hands-on work go hand in hand. That feeling of curiosity, of discovery, and yes, even of play. It’s all part of what makes the scientific journey so fulfilling.

I agree! You went from molecular biology to neuroscience to engineering. Would you say fun is the common denominator here?

I think so, yes. For me, whatever is fun tends to be interesting enough to pursue. But fun isn’t always immediate or obvious, it often emerges when the right elements come together: a setting that sparks curiosity, a topic that clicks, a compelling question to explore, and those small moments of success along the way. When that happens, the work becomes deeply rewarding. That sense of enjoyment has definitely been a guiding thread through the different stages of my journey.

I see! And when did you first encounter MaxWell in your path?

My lab started back in 2014, hard to believe that’s already more than a decade ago. In the beginning, it was just me. By the second year, there were three of us, and from there the team slowly grew. At that time, I wasn’t getting many unsolicited emails, the kind that tend to flood your inbox nowadays. So, when I received a message from Marie, I responded. It turned out that the technology Marie introduced sounded genuinely compelling. It all just seemed to align in an unexpected but meaningful way.

And from this first encounter until now, how has MaxWell technology impacted your field of research?

When I first moved into neuroscience during my postdoctoral training in the U.S., I wasn’t formally trained in electrophysiology. I learned only a bit of clamp experiments, but my main focus was on neuronal morphology, understanding how axons grow and form connections. However, in this field, gaining insight into network activity is essential. While patch clamp can provide valuable data, it’s technically challenging and limited to single-cell readouts.

At that time, I became aware of conventional MEA (microelectrode array) systems, someone at Harvard was already using one, and I thought it was a very cool approach. So when I returned to Japan, I felt the need to expand my toolkit. I wanted a new way to observe and understand neural network activity, something reliable, accessible, and suited to complex systems. That’s where MaxWell’s technology really stood out. Its commercial availability and high-density capabilities made it exactly the kind of platform I needed.

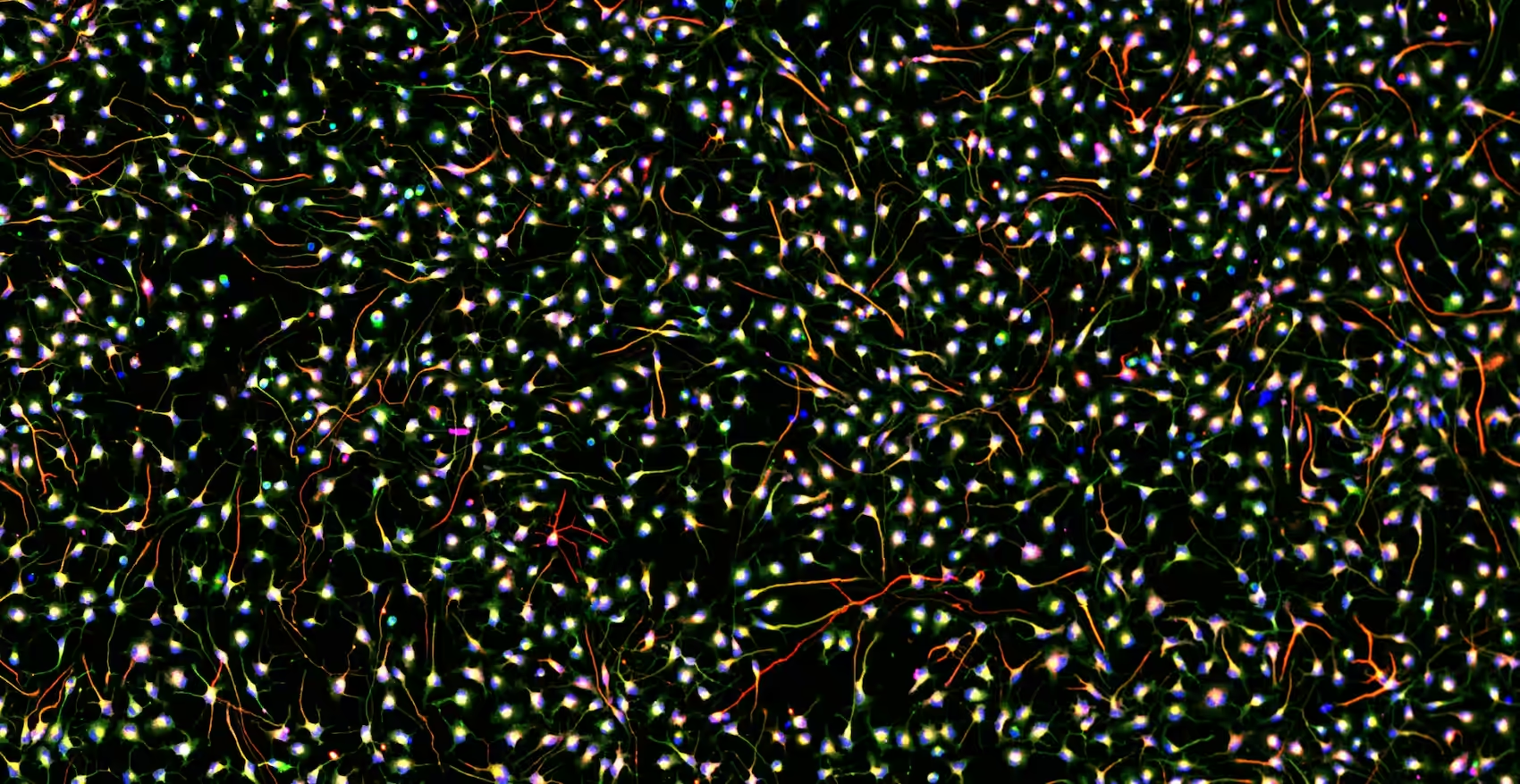

Today, our MaxOne System plays a central role in our work. In fact, it has become a defining element of our research. It allows us to grow organoid-derived neural networks directly on the array surface and record their activity over long periods. This enables us to observe temporal-spatial dynamics, correlations, and sequential patterns of activity, all within a single, integrated system. Given the complexity of the networks we’re studying, the fact that the technology is also easy to use makes it even more valuable.

And what are the major challenges you were able to overcome using our technology?

That’s a great question. Honestly, if we hadn’t had access to electrode array technology, I’m not sure we would have even considered some of the research we’re doing now. Maybe my brain has become a bit spoiled by the possibilities this technology opens up!

Let me take you back a few years, around 2017. At the time, we were working on a motor nerve organoid model for ALS, which we’re still developing today. The goal was to mimic an axon bundle stretching from the spinal cord to the muscle. We performed a few gene knockdown experiments to see if they would lead to reduced axon growth, but when we tried to monitor neuronal activity using calcium imaging, we hit a wall.

The problem was balancing scale and resolution. We wanted a broader field of analysis to capture the overall activity, but we also needed fine spatial resolution to pinpoint where exactly that activity was happening. With calcium imaging, all we could really see was a single large burst across the entire organoid—there was no way to resolve individual cell-level bursts. We tried using different objective lenses and even built a hybrid setup with both inverted and upright microscopes, but it remained extremely challenging.

Those limitations were exactly what the high-density MEA (HD-MEA) technology helped us overcome. It gave us both the scale and the precision we needed, allowing us to track detailed neuronal activity across a wide field, and ultimately enabling a level of analysis that simply wasn’t possible with our earlier tools.

That’s very cool, thank you for sharing. Then, of course we are curious—what’s next?

That brings us back to the earlier question: what’s the purpose behind all of this? Our overarching goal is to understand how neural networks function and interconnect. But we don’t want to stop there. We also want to explore how we can actively modify these networks using stimulation, and ultimately influence their behavior in meaningful ways.

To move forward, we know what needs to be done. We need to develop better tissue: cells that are more mature and capable of truly mimicking brain functionality. That level of biological fidelity is essential if we want to model complex conditions, like psychiatric diseases, in a meaningful way.

Right now, I recognize that some of our work is still in its early stages, it’s the “baby stuff,” so to speak. But even so, I want to make sure we’re doing something useful along the way. Ideally, we’re laying the groundwork for building networks with greater functional complexity. And from there, we can start imagining bigger possibilities, like the idea of building a computer made entirely of living cells.

Of course, accomplishing all of that would be amazing. Back to MaxWell: what is your favorite feature of the technology?

Honestly, I like everything, it really is the full package. All the features come together in a way that makes the system incredibly effective. But if I were to highlight something that might set my perspective apart from that of a typical user, I’d say it’s the flexibility to program the system exactly the way you want. That level of customization is powerful. And at the same time, simplicity plays a big role: the fact that everything can be controlled seamlessly from the computer makes the entire workflow smooth and accessible. It’s a rare combination of power and ease of use.

And if you could design your own, dream MEA, what would you add?

If I could design a dream MEA, it would be one that could record from the entire organoid, both inside and out. Being able to capture activity at every location, would be incredibly powerful. Of course, that sounds a bit far-fetched with current technology. One of the key challenges is accessing internal regions without disrupting the organoid’s structure, which is why surface recordings are so valuable.

Lastly, what has your experience working with the MaxWell team been like?

I’d describe the relationship as being rooted in shared core values. We’re aligned not just in how we approach science, but also in how we appreciate the day-to-day aspects of the work. What really stands out is how easy it is to reach out, ask questions, and exchange ideas. There’s a natural, easy-going pace to our interactions that makes collaboration both productive and genuinely enjoyable. That kind of atmosphere is incredibly valuable, especially when it comes to developing and refining complex technologies together.

Thank You!

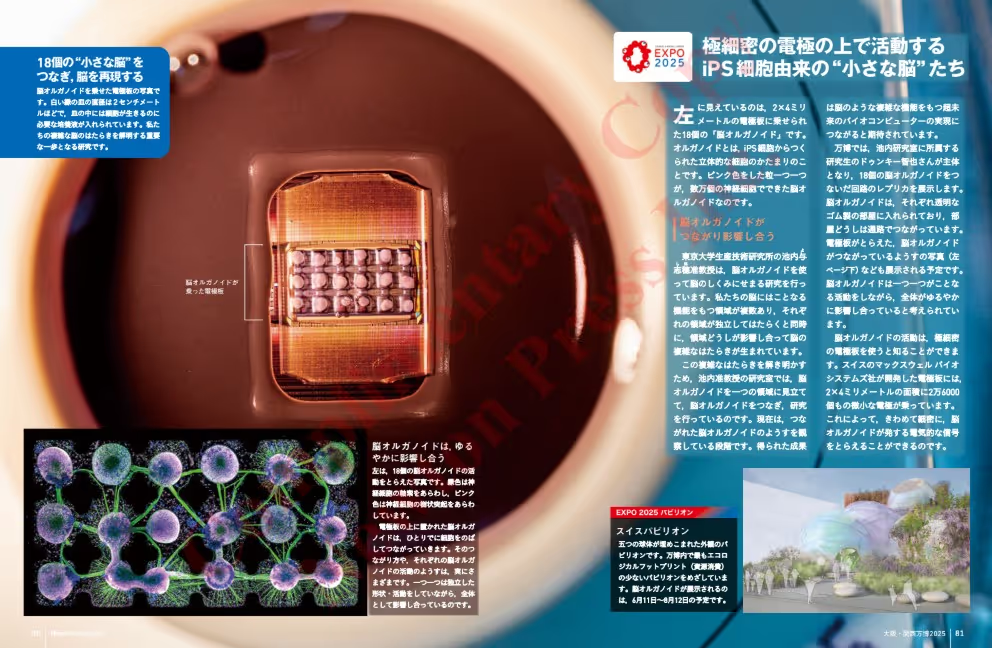

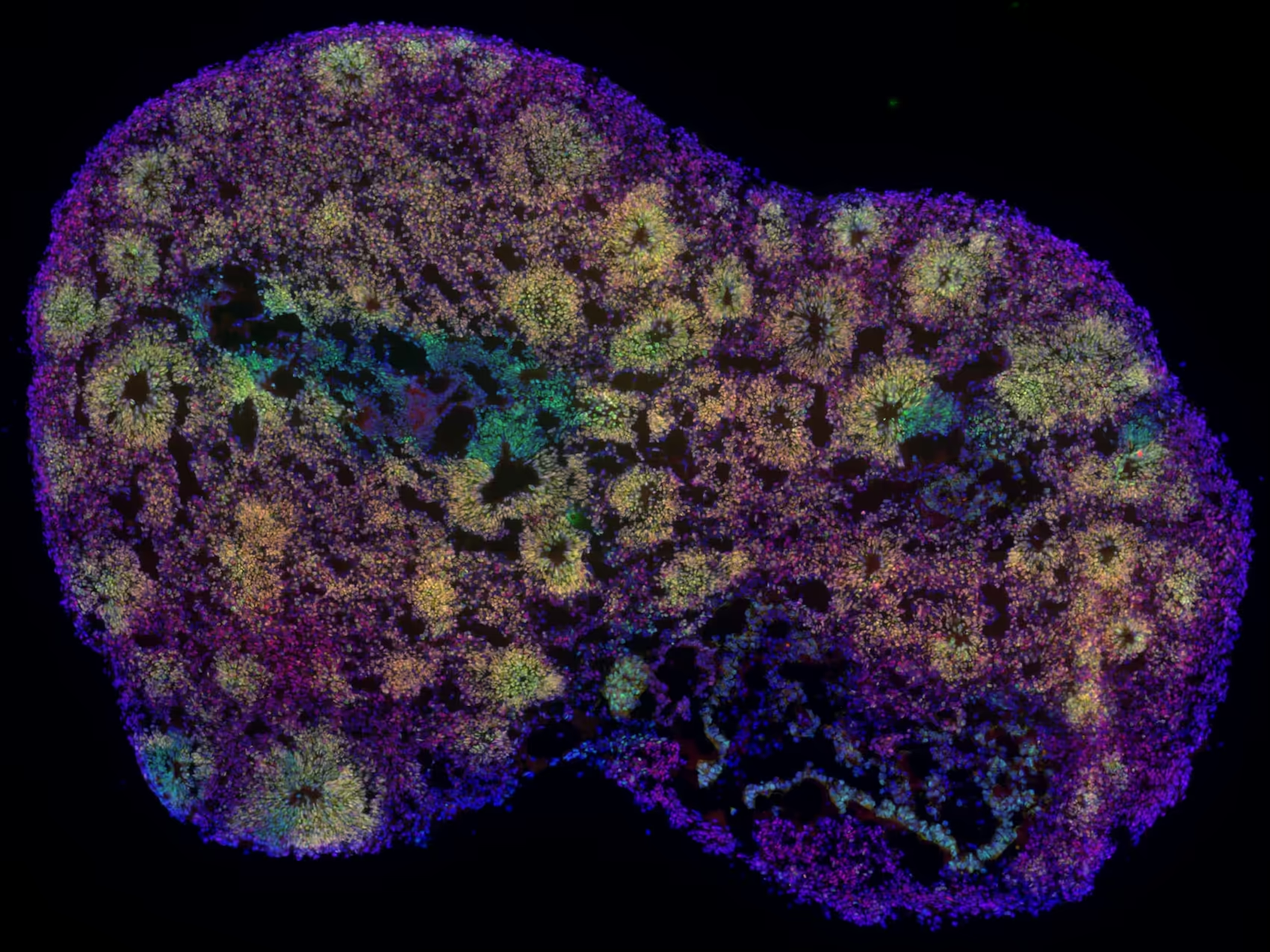

We’ve had the privilege of joining Prof. Yoshiho Ikeuchi and other leading experts in insightful discussions about the challenges and future of neural cell functionalization at the University of Tokyo (see image 1). Together, we’ve also helped bring these complex topics to a wider audience at BeyondAI (image 2), turning cutting-edge science into accessible learning moments. One of the most exciting highlights has been the feature of Prof. Ikeuchi and Dr. Tomoya Duenki’s “tomorganoids” in the renowned Japanese science magazine Newton. These fascinating brain organoids were visualized on one of our MaxOne chips (image 3), a stunning image that will be showcased live at the upcoming Expo in Osaka. We’re truly thrilled to see where our next joint endeavors will take us!

We would very much like to thank Prof. Yoshiho Ikeuchi for making time to take part in this testimonial. We are very appreciative of this collaboration.

If you would like to learn more about Prof. Ikeuchi’s work with our HD-MEA systems, watch his recent webinar.

If you are interesested in more details, please contact us through email via info@mxwbio.com or schedule a call with one of our experts.

Discover More

MaxOne

Versatility and functionality in one compact device

MaxLab Live

All-in-one Software

Organoids

Neuronal Cell Cultures

Biocomputing

BiœmuS: A new tool for neurological disorders studies through real-time emulation and hybridization using biomimetic Spiking Neural Network